My last couple of blog posts have been a bit downbeat, maybe to the point of being a little depressing. Reading about self-interested and dishonest producers and the horrible cull choices that we face as farmers may be informative, but it really doesn’t make you feel good about the world, does it? I just realised that I have another post queued up and ready to go (the weather isn’t being kind to me and I need some kind of farming outlet 🙂 ), and it may be even more depressing. I figure it’s time for a more uplifting post, so I’ll put my latest depressing post on hold and write a more cheerful one. Full disclosure though – I expect this one to maybe start off a little depressing, but it’ll finish with lots of piglet pictures. Yay for piglet pictures! 😀

Also, that was all less me noticing and deciding than it was Linhda pointing out the obvious to me and suggesting I do something more cheerful. 🙂 Either way, here goes…

When we first bought pigs the breeding part seemed pretty easy. You get a couple of healthy young girls, you put them in with a healthy young boy, and about four months later you have more piglets than you know what to do with. What could go wrong? As it turns out, there are lots, and lots, and lots of things that can go wrong. I know that because I’m pretty sure we discovered them all the hard way. 🙂

As with everything I do, I researched pig breeding thoroughly before we had a go. I read everything I could get my hands on, and we were pretty much as prepared as any smallholder could be. We were committed to providing the safest facilities while maintaining our free-range vision. We set up a farrowing shed and free-range yard with piglet-proof fencing, or at least what we thought was piglet-proof fencing (spoiler alert: it was not in the least bit piglet-proof 🙂 ). We set up a creep area in the shed with supplementary heat so the babies could scooch away from mum if they had to. We made it super comfortable with bedding, and even put in lean boards around the inside of the shed – kind of like a sleeper retaining wall on the inside of the shed so mum could have a scratch and not bust through the wall. We then got the vet out to give it all the once-over and suggest any changes. His single change was that we lower the heat lamp a little. We ended up with a luxurious piggy condo that would make any expectant mum happy. Well, happy if she were a pig. 🙂

Just to be clear, by “shed” we in no way mean a contained, concreted area. It was a dirt floor with lots of bedding, and the mums had full access to the outside. That’s still the way we build them too.

Lean boards are important. We’ve had a girl simply walk through a shed wall once when she couldn’t be bothered taking the extra two steps to the door.

The creep, before we put the heat lamp in. You can see how babies can easily get away from mum.

The girls and Boris checking out the new farrowing yard digs, just before we put the bedding in there.

The first problem we faced was with assessing when the mums were due. We had two girls pregnant at once – Honey and Smoked. We knew the gestation, and using my mad spread sheet skills we were able to fairly accurately calculate the due date. The problem was that we didn’t think they were both the same amount of pregnant (yes, that’s a medical term). Smoked was WAY bigger than Honey, though both were clearly pregnant, so we figured that Honey hadn’t taken on the matings we witnessed and must be a full cycle (3 weeks) out. With that in mind, we popped Smoked into the farrowing yard so she had access to the shed, and put Honey in an adjacent yard. Honey had full access to shelter and bedding, but it was nothing like the 5-star accommodation her sister was enjoying.

I remember going out on a chilly September morning to check on Smoked. I knew she was due any day, and her giant belly and full teats were testament to just how imminent were our first babies. What I didn’t expect to see was little pink wobbly things wandering around Honey as I walked past. Not only were both girls exactly the same amount of pregnant, Honey, the smaller mum, had 10 babies to Smoked’s 6. Both on the same night.

We scrambled to get Honey set up with some semblance of a creep and heat for the babies. Now, not every free-range pig farmer uses farrowing yards, sheds, creeps, or supplementary heat. In fact, there are some who refuse, opting rather to have a completely natural farrowing experience for their pigs. The standard we follow, Pasture Raised On Open Fields (PROOF) has a lot of proponents whose pigs farrow in the middle of a paddock. That standard absolutely allows for farrowing the way we do it, and our girls have full access to the outside almost 100% of the time. I say “almost 100% of the time” there as we occasionally contain a girl for a day. This will be if the piglets have proven to be super active, and are deciding to wander outside on a cold day where mum clearly doesn’t have the energy to go watch them. In these cases, we block off the entrance into the free-range yard and keep the mum and litter inside the (large) farrowing area.

The supplementary heat really is a big help. These babies are safely away from mum should she roll.

They do love to pile on top of each other under the heat lamp.

We’ve also farrowed girls in paddocks ourselves, but have still given them portable shelters with bedding. The biggest difference there is that they don’t have creeps or the supplementary heat that encourages the babies to snuggle up in the creep. That’s worked quite well, and we’ve never really had a problem with it. Even the girls in our farrowing yards have the option to drop outside if they want. They’ll build a nest wherever they want, and there’s not much you can do to change their minds. 🙂 To date, every girl has chosen to drop inside though.

Our main reasons for having covered areas with creeps and heat etc. are:

- The creep helps reduce mortality in the babies. I know the same argument is used for farrowing crates, but you can’t compare the two. The babies are free to go back and forth, the mum is free to wander outside, but the creep gives piglets a protected area should mum be a bit careless.

- The creep allows us to feed the babies away from mum if we have to. Most mums are really good and their babies always get a good meal. Sometimes though, you might get a mum who is a bit of a food hog (pun fully intended) or maybe a baby who is a bit small. Being able to feed them away from mum, while still being right next to mum, can be helpful.

- The way we’ve designed the creeps means that we can get in there, or lean over the fence, and interact with the babies safely away from mum. The tamest sow in the world will have a go at you if you mess with one of her babies. They’re fine if you pat the babies. They’re fine if you pick the baby up. The second the baby squeals though, she goes into full protection mode. Having babies away from mum can be helpful.

- Having the mums effectively indoors in inclement weather has obvious advantages. Our shed isn’t climate controlled, but the shade and shelter really are helpful.

- Having the mums all in the same area is surprisingly helpful when it comes to feeding or even moving them. The same goes with the babies. Trying to herd a litter of piglets over a paddock is about as painful as it sounds.

Basically, farrowing the girls in purpose-built areas, with the creeps and heat, gives us all of the advantages of a free-range environment without many of the problems of an entirely pasture-raised environment. The pigs have full access to the outside and forage, but are still protected.

This is Frankie’s litter, and it demonstrates one of the features of our new farrowing yards. There’s a concrete footing around the outside of the shed, and it’s good for keeping the little ones in for a few days. From memory, Frankie’s babies were several days old before they ventured outside. Then again, we’ve had hour old saddlebacks recently who managed to climb the same ledge. 🙂

Anyway, back to Honey. We could’ve just left her where she was, but it was cold and we wanted to make sure the babies had as much protection as we could muster. We rigged a creep and heat in Honey’s shelter, and it worked quite well.

This is the creep area we quickly rigged. There’s a green pole keeping Honey from stealing the heat, and put the box in there to better focus the lamp. The nights were frigid, and this was the best way to keep the babies toasty.

Connie and Gemma hanging out with Honey and her babies. The babies are a day or two old, but since then we’ve hung out like this with Honey as she’s delivered each litter.

We lost one baby out of that first 16, leaving us with 15 weaned babies. Even with the running around to get Honey unexpectedly set up, everybody was happy, we had babies everywhere, and we figured that this pig breeding thing was pretty easy.

We quickly learned that it’s not all sunny days and piglets. We ran into a number of problems after that initial honeymoon period, both in terms of sow pregnancies and piglet mortality. These included:

- Smoked came up lame, and after we nursed her back to health she still couldn’t get pregnant. I explain this in detail in my post on culling sows, and after many, many, many chances, we decided to cull Smoked. 😦

- Honey came down with pneumonia. We nursed her back to health too, which took a full 12 months, after which she was healthy enough to breed again. I talk about that in the culling sows post as well.

- We lost pregnant girls to the Pinery fires. In fact, two out of our three pregnant girls, Honey being the lucky third, had to be shot after the fires. Literally, two-thirds of our production was wiped out. That’s clearly not a husbandry practice we could change, but it did show us the value of redundancy.

- Believe it or not, we had a boar with short legs. 🙂 We picked our boar from a group of boys we had – he was the biggest and just generally the best looking boy. When he and Smoked and Honey were younger, he had no problem doing the deed. However, both of those girls outgrew him, and both were quite tall. In the end, Boris simply couldn’t get the angle of the dangle right (if you know what I mean 🙂 ).

I make light of this, mainly because it’s funny looking back, but this was a surprisingly tough problem for us to identify. We have a fit, virile boar who is clearly mounting the girls. We have girls who are clearly in season and encouraging the boar to do his thing. And we were getting sporadic pregnancies, but not the frequency we expected from the matings we witnessed.

We ended up diagnosing it after watching one of the sows (Ziggy I think) stand in a hole to let Boris climb on board. It made me laugh at the time, but then I watched more closely and it was clearly a thorough coupling. We then watched him with another girl, not conveniently standing in one of the giant paddock divots they like to create, and he was missing the mark. It then dawned on us what was happening. Boris was going through the motions, and obviously enjoying his time, but that wasn’t going to make babies.

We learned to look for what we call “P in V”. 🙂 We have a farm FB chat group through which the family communicates, and where we swap pictures and basically keep everybody in the loop on a daily basis. A common interaction is to send a picture of one of the boars mounting a sow, like you do, and the instant question is always “Did you see P in V?!”, or sometimes just “P in V?!”. We now get up close and personal to check for the thoroughness of the coupling. If you don’t see P in V, then it’s not a confirmed mating.

In short, Boris was stubby in the legs, and our sporadic pregnancies were because sometimes he was lucky enough to get a girl standing in way that allowed him to get up high enough. For anybody who thinks that P in V talk would make you uncomfortable, never come to dinner at our house…

- Age can play a big role too, in both genders. Older girls have smaller litters and struggle more with it. In an intensive context, they never get old enough to really show that, but in an extensive farm like ours, you’ll get girls who start to show a natural decline in their fertility.

The same can be said for boys. Older boys both lose some fertility and some energy.

- Too much weight can be problematic, again in both genders. “Eating like a pig” is an insult for a reason. Given the chance, most pigs will gorge themselves, and really aren’t concerned about their figures. This can be a problem with growers, as the resultant meat is fatty. You can get around that though, by trimming chops etc. It’s wasteful, but not insurmountable. With the breeders, however, it can have a huge impact to their fertility.

We’ve personally found weight to be a problem in both sows and a boar. Reggie, our big saddleback boy, hadn’t worked in several months before we got him, and wasn’t exactly fighting fit. We watched him with the girls. Now, boars will ask the girls a question if he’d like to mate. Those girls will tell him unambiguously if the answer is no. Seriously, there is no messing around if the boar is interested and she is not. No really means no when you’re a sow who isn’t in season. On the other hand, if the girl is in season, she can be almost equally insistent that the boar hook her up. She’ll nudge him, grunt at him, and even try to mount him and each other (leading by example maybe?) The other thing of note is that a fit boar will mate a number of times in a relatively short period. It might start with the girl asking the boar for some attention, but sometimes after the fourth or fifth time, she’ll be asking him to quit it.

With Reggie, he’d never ask the girls the question but the girls would ask him, he’d sometimes grudgingly get up, struggle to mount, and then he’d go lay back down again, clearly out of energy. The girls would be nudging him, wanting more, but he’d invariably lay there, soaking up the sun, and generally looking like the giant stud that he wasn’t.

The other point of concern with an overweight boar is the sow/gilt being able to take his weight. That hasn’t been a huge problem with us, as our girls are generally chosen to be quite large and sturdy. It can be a risk though and needs to be considered.

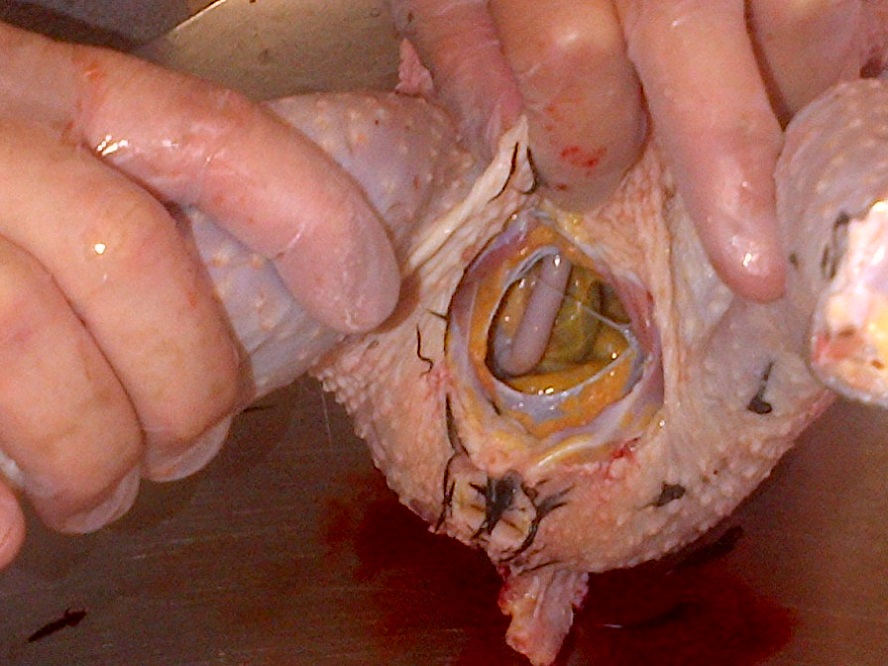

With the girls, the problems are around fertility and being able to carry healthy babies. It’s tough to tie down the exact fertility problems, but the fatter girls have a harder time getting pregnant. That’s not a very empirical analysis of the situation, but it’s true. 🙂 The problem with carrying is weird, and also super freaking gross. We had a couple of girls give birth to these half-formed, alien-looking babies. My first theory was that they’d had congress with a demon, but the vet quickly disproved that theory (spoil sport). Apparently, sometimes when there’s not a lot of room for the babies to grow, you’ll just get some that don’t really develop. We’ve only seen it a couple of times, and we’ve seen it in girls who were too fat and in a girl who had a huge litter (and was also a little fat). I’d post a picture of one of those babies, but it would give you nightmares.

- The flipside of being too fat is being too skinny. We’ve not really had that problem with the breeders, but we definitely had a short stint where our nutrition wasn’t right. I bang on about nutrition in other blog posts, and it’s something we feel very strongly about. We’re not going to go the easy commercial food route for a whole range of reasons, the topmost being that it’s not a sustainable way to grow anything. The downside to that was that it took us a few months to get it right, and in the meantime we had some pigs lose condition. They were happy and healthy and eating their fill, but they weren’t growing the way they should. This includes the breeders, and we noted a downturn in fertility.

- Piglet mortality is a bit of a hot button topic in our world, and is one of the biggest points-of-difference between intensive and extensive farming practices. Intensive farms use farrowing grates or sow stalls because they reduce piglet mortality. Extensive farms like us range from not employing any interventionist practices at all to doing what we do, with creeps and heat etc. In our experience, following our practices can give some excellent results. The industry average is, I believe, 10% to 15% mortality, and we have girls who over their lives are well in that range. However, we’ve also had a couple of examples where it’s much higher.

The first of those was with Ziggy and Stumpy, the two girls we ended up losing as a result of the fire. We’d visited an interstate pig farm who farrowed their girls in pairs. That sounded like a great idea. Pigs are gregarious by nature, and love company. We went home and built a farrowing shed designed for girls to share it. It was a feat of engineering, and had a double creep, angled so the girls could both use it at the same time. The problem was that our girls wanted to spoon the entire time, and we ended up losing around 40% of those two litters.

For the record, I suspect what that other farm did was farrow the girls separately, but then after a shortish time let the girls in together. We’ve done that ourselves since with no problems.

We also had a problem with an aggressive mother, our only aggressive sow ever, who trampled her babies trying to get at us through fences. She ended up with 2 weaned young from a litter of 13.

We get stillbirths and squashings, but not a huge amount of either. If we have a litter in the double-digits, then you’d expect maybe one or two losses. For the most part, our mortality problems have been due to practices that we’ve had to modify.

- Small litters are also painful. We’ve had litters of 13 multiple times, and often get double-digits. However, we also have had girls have only a couple. This has been either an old girl, a young girl, or a fat girl. The first one and last one we can fix – we retire the old girls (that was an accidental pregnancy) and we keep our breeders trim. The young girl is part of what we do though. You’d expect a first litter to be a bit smaller, especially from a heritage breed, and you’ll give that girl a second chance. By the same token, Frankie, one our favourites, had 13 in her first litter. It can be hard to pick. 🙂

So that is a laundry list of about everything that can go wrong with breeding pigs, from fertility to litter size to piglet mortality. We’d read about some of the problems, but we encountered them all. Much of that followed the Pinery fires too, which is when we lost most of our pregnant girls, meaning we had a real slump in production. That’s the depressing bit of this post that I warned you about at the start. 🙂

We’ve adapted our practices a fair bit, while remaining true to our vision of ethical farming, and the results have been great. At the same time, we had to hustle to fill our gap in production. The things we did were:

- Early on we bought in weaners to fill the gap in production. We found a couple of smallholders who bred pigs and sold the babies rather than feeding them on as growers. We were careful to find people who did this in a way that matched our ethos. This worked quite well, and not just because we were able to address our production slump. Both of the people we bought from, and still do buy from, had heritage breeds that we wanted to try. One breeds Berkshires and one breeds Tamworths, and we’ve used piglets from both as our own breeders.

Right now we don’t really need to buy in any more piglets, but I still get them from these same people. I like having a trusted source, and I don’t yet have enough Berkshire or Tamworth breeders. I’m keen to keep an entire boy from both too.

We also bought in an entire breeding herd of Wessex Saddlebacks – six girls and one giant boy. They’ve done well by us, and Reggie is still one of my favourites. 🙂

This is the big man Reggie! His pedigree name is Dominator. It looks like it suits, but he’s really a giant puppy dog.

- We joined the Herd Health Management Program at Roseworthy Vets. This covers all of our animals too, not just the pigs. We get quarterly visits, and then visits whenever we need them. We tend to time the visits for when we want pregnancy tests. I still keep a mean spread sheet that will predict farrowing times, but we don’t get to see a lot of the matings. We’re also pretty good at picking pregnancies, but for some girls it’s really hard. For example, Betty, who is actually due to drop in a week or two, was pregnant about 10 months ago. We thought she was pregnant, but with the Saddlebacks it’s just really hard to tell (they’re kind of thick and round to start with). Then, one day, we saw her standing still so Reggie could mount her. That was it – she was clearly not pregnant. Three weeks later she had babies squirting out of her in the middle of one of the paddocks. She hadn’t noticeably bagged up with milk, which is the surest sign of imminent birthing. She’d stood still for the boar, which is something I’ve never seen a pregnant girl do. She’d clearly wanted to mess with us. Having semi-regular pregnancy tests has proven really helpful at times. Also, not cool Betty…

- We expanded our farrowing infrastructure. We have a huge implement shed on our new place, and we stole the length of one wall to build farrowing yards. Each has a free-range paddock attached to it, and we’ve run electricity and water to each. These are super sturdy and pretty luxurious. We’ve seen a lot of small holder set ups for pig breeding, and we’re yet to see one that is as nice as this. That sounds immodest, but you’d be amazed at some of the things we’ve seen. Our farrowing area is like the Piggy Ritz. 🙂

We plan on expanding these farrowing yards even more. We thought that having 4 would be enough, but we’ve already had an instance of 5 mums in 4 yards. That worked quite well at the time as two of the girls lived their whole lives together (and still do), and so were able to share once their babies were a couple of weeks old. We also have the option of having them farrow in a paddock, as we have what we call “maternity wards” set up – portable shelters and the ability to fence off smaller areas with portable electric wire. Having more farrowing yards makes sense though, and helps to future proof us.

- We fixed our nutrition. I’ve banged on about this a lot, including the blog posts that I mentioned earlier, but we have really put a lot of work into getting this right. It’s ongoing work too, as we have to manually make their food weekly or fortnightly, and we’re always tweaking what we make and how much we feed.

Getting the nutrition right fixed almost all of our problems, both with growers and breeders. So many problems can be linked back to the animal’s feed. This would never have been a problem if we just bought the commercial feed, but I was determined to do this right. That determination almost sent me completely grey, but it paid off in the end. 🙂

It’s not just the feed mix we had to get right either, but also the amount. This is complicated by the fact that we feed out brewers mash as well. The mash can make up half of their ration, but we make the halves unequal (any mathematician reading this just flinched a little). For example, if a dry sow’s maintenance diet is around 2.5kg/day, we’ll feed them half of that in milled feed but will then give them as much mash as they like. The mash is relatively denuded of nutrients, but has lots of roughage. They get to fill up, but not get fat. We’re able to tweak this according to the pig’s condition and breed, with heritage breeds requiring a much smaller nutritional profile than white pigs. So it’s kind of half milled food, and HALF mash. 🙂

This also helps us grow the pigs slowly. If we fed the growers ad lib on the milled feed, they’d get to size much more quickly. The heritage breeds would quickly get fat, but they’d all get to a consumable size quickly. We don’t want that though. We don’t want piglets that are ready to go after 4 or 5 months, regardless of their breed. We want even the white pigs to grow more slowly. The end result is more cost to us, but it’s a much, much better product. We have better marbling and a superior taste.

I’ve spoken before about our conversations with nutritionists, and just how badly they have sometimes gone. We did find some super helpful ones though, who were able to give us great advice while still respecting our goals. One of the awesome things they told me was about feeding the pregnant girls. Our dry sows and the boars get that maintenance feed of 2 to 3kg per day. It doesn’t sound like much, and would actually leave them hungry. Being able to throw mash at them to fill them up makes that all workable though – our aim isn’t to have hungry, unhappy pigs after all. Our growers and lactating girls get pretty much whatever they can eat (ad lib feeding). The difference was our pregnant girls. We were treating them like lactating girls, and giving them way more feed. The nutritionist told us that the pregnant girl should be treated like a dry sow up to the day she drops. Basically, we were overfeeding the pregnant girls by a fair margin. Now, to be 100% honest, our pregnant girls still do get a bigger ration, but it’s nothing like we used to give them. We’re all suckers for those big soulful eyes… 🙂

Small growers chowing down. That giant paddock behind them is all theirs and has lots of feed. However, they really don’t get much of their ration from forage. They need a fair bit of supplementary feed, and we’ve now gotten that right.

- We’ve changed our strategy around the breeders. This is in a couple of ways:

- Our original aim was a production level of 12 sows and 2 boars. It’s a good and manageable boy/girl ratio, and the output would be about what we needed to meet the demand we were aiming for. We were going to take time to get there of course, as the production had to grow with the demand, but that was our aim.

What much of the above taught us was that we need redundancy. At first I worked up a spread sheet that showed the mating rotation, followed by the farrowing rotation, in a herd of our ideal size. It showed how long we’d have the girls in the farrowing yards, and then how we’d rotate the weaners out. It was like a mathematical ballet in excel and it was beautiful. Of course, it was never going to work. It never took into account what would happen if only one girl in a pair was pregnant, or if three were pregnant at the same time for that matter. It never showed what would happen if one boy was a dud, or if we lost a girl for any reason. It didn’t show what would happen if you had a fire destroy most of your property. It was basically a best-case scenario, and belongs in a world of pixies and elves.

The thing missing was redundancy and adaptability. You might need 16 girls and 3 boys to get you the 12/2 production level. You’ll have times where you need to shuffle things around because you have too many pregnant girls and times where you have none. You’ll have girls who look pregnant, but who are messing with you. Or you’ll have a Betty who is the opposite. You’ll have huge girls give you a handful of babies, or much smaller girls give you a dozen. You have to be able to adapt to any of those situations, and be ready to adapt to anything else that a crafty pig decides to throw at you.

We currently have two working boars, Reggie and his son Lazarus. However, I also have two on the way up. One is a Large Black boy, Piggy Smalls, whose mum, Lulu, was pregnant when we got her, so he is virtually fresh genetics for us. The other is a half white, half heritage (blue merle) boy named Notorious P.I.G. Both of those boys are a few months from being able to produce young, but they’re our redundancy. For one, I’m not sure how much longer Reggie will be productive for. The old boy is definitely slowing down. For another, they give us the chance to try a heap of different breed crosses.

Along a similar vein (I love on-purpose mixed metaphors), we’ll be getting in a handful of new Tamworth piglets shortly. We currently have two litters on the ground from two Tamworth girls, with Lazarus as the dad, and I’m keen to keep an entire boy from this new lot. We castrate young, and so have to pick any potential boar early, which can be difficult. These Tamworths will be a couple of months old, and we’ll be able to better pick the best boy.

We’re also picking multiple girls as potential replacement breeders. This is much easier, and in reality, almost any girl of breeding age is a potential replacement. 🙂 We do like to pick them young though, so we can make sure that they’re super tame.

Basically, we always have a pipeline of upcoming potential breeders of both genders.

Half of the saddleback girls we bought in. They gorgeous!

This is Ginger. She’s given us two great litters and is more than likely pregnant with her third. She’s a good girl.

- Linked to our decisions around culling breeding stock is our decision to cycle through breeders as necessary. I’m hopeless for giving the breeders second, third, and fifteenth chances. And while we have that ability, it hurts our production. A better way forward is to give the breeders those chances, but swap another in to fill the gap. That’s a bit harder with the boys, as a dud boy with 3 or 4 girls means a dud 3 or 4 girls too. Still, our plan is to change our breeding paddocks to contain groups of 3 or 4 sows/gilts, move boys in as required, and use the up-and-coming breeders whenever we can.

Another thing I tend to do is give the girls longer breaks between litters. Part of that is because we ween later than most (8 to 10 weeks), but also because I’m happy to give them a rest if we have our quota of breeders in a breeder paddock. A combination of longer breaks, longer weening, and multiple chances means that we effectively need more breeders. From a purely commercial point-of-view, it means we end up with non-productive time in our breeders, which is equivalent to non-productive breeders. From our own ethical point-of-view, I don’t care. 🙂 I’m going to give my girls breaks, give my piglets more time, and give all of the breeders as many chances as I can. I’ll just keep more breeders to make up for it.

This is Lulu’s first litter. She had 1 boy, who we decided to keep as a boar. He’s Large Black and mostly unrelated to all of our other breeding stock. We’re also keeping at least 2 of the girls, Evie, the largest black girl, and Liv, the liver coloured girl on the end.

Tammi, one of our new Tamworth breeders. She had 9 in her first litter, with all surviving.

Most of the activities described in the above wall of words we’ve done or are doing, and some of it we’re in the process of implementing. It’s a constantly moving feast though, and we’ve learned to change as required. Right now it’s working well too! For the first time ever we have a small glut of pigs, and we’ve been able to reach out to our restaurant network and offer them pork again. More than that, the quality is consistently excellent. In the past, we’ve taken pigs that I wasn’t 100% happy with, as it was that or take nothing. Variations in production and even quality are to be expected with people doing what we do the way we do it, but it hurts having no pigs to take. In hindsight, there were a couple of times I should’ve taken nothing rather than something inferior, but that’s one of the lessons we’ve learned. Maybe there’s a blog post in it. 🙂

And now for the promised piglet pictures…

Tame pigs means tame-ish piglets which means lots of piglet close-ups.

Part of Ginger’s first litter. These were born outside in one of our maternity wards.

Honey’s first litter taking breakfast outside. 🙂

A free-range pig is rarely a clean pig. 🙂

They are SO small when they’re born. It doesn’t last though.

Want to tame a pig? Hand feed it food. You’ll be friends for life.

And they all love having their butts scratched.